Maverick Moves

On my journey through unknown airspace I invent some aerial manoeuvres.

About ten years ago I came to the conclusion that I make my own stress. I was going through a period of intense anxiety, I’d lost my right to work while living in Seattle, USA. I felt completely victimised by a situation which was outside of my control. You-Know-Who had changed the immigration policy and I was furious about it. I also had a beautiful tiny baby to look after, so I needed not to be angry all of the time. Finding a new perspective during that time helped me to find a more balanced mindset.

My work-visa was derailed during my professional coach training, which put my qualification at risk. Being coached was part of the training, so I asked my coach to help me find a way to cope with the situation. Since it was not going to resolve itself, I needed new ways to think about it. I discovered that if I believe I make my own stress, then a seemingly helpless situation feels more within my autonomy. That coaching conversation helped to put my hands on the lever, and gave me command of a way forwards. I was more able to navigate the challenging conditions by manoeuvring my reaction to the situation, and reclaiming my self-authority. Today I found myself saying it again.

Cruel Restoration

During sunrise yoga this morning, my mind gently moved through its own quiet musings. I love the way that controlling my breath for an hour helps my brain to slow down. Breathing properly helps me to think straight. At some point in my meditative movement my subconscious delivered a thought, “I make my own anger.” I realised that I’ve been feeling angry recently because I’m angry at myself for moving on without Mark.

This week I’ve been deeply involved in back to school activities, returning to work meetings, getting life admin done, and building new shelves in my lounge. These book shelves were the final unfinished part of our house renovation. We didn’t have the money to do them at the end of the project, so we waited a few years. We commissioned them last October to give ourselves a sense of completion while Mark was sick. Then everything changed with his health and the shelves were forgotten. I was happy to be moving forwards with them now, I’ve been longing to get my books out of the attic. It was lovely to have our friendly builder back in the house. We chatted over coffee, podcasts, and paint colours. But the shelves are up now, the project is done, and Mark’s not here to see it. These returnings and restorations in our everyday life are wanted. They’re also very painful to live with.

Angry Again

I wrote last week about the anger of grief. Since then I’ve been reflecting on how I repress anger, when it’s healthy, and perhaps when it’s not so good to hold onto. If I’m saturated with anger I’m impatient, which means I’m less good at my job. To be a good listener I need patience. When I get annoyed for small reasons my kids begin to feel blamed. I notice that I find it hard to speak with close friends and family when I feel enraged, because my rage frightens me; I’m terrified of what might happen if I let my true anger slip out of me.

I walked up a hill on Wednesday and shouted at the wind, from Mark’s favourite bench. By the time I got to the school gate I must have looked like a banshee who’d been dragged through a bush backwards, because one of the parents said, “You look wild. Are you OK?” I took it as a compliment. On several occasions I screamed into a pillow with my kids. I think we all slept better with a bit of bedlam in our bedtime routine. I also booked myself onto a CrossFit trial next week, to see if a high intensity workout will get this fury out of me. In addition to taking the conversation into my Cruse counselling session this week, I went to yoga this morning for the second time this week, with the explicit intent to address my anger.

This wild woman means business. Bereavement may get the best of me, but I will not let it keep a hold on me.

The Middle Zone

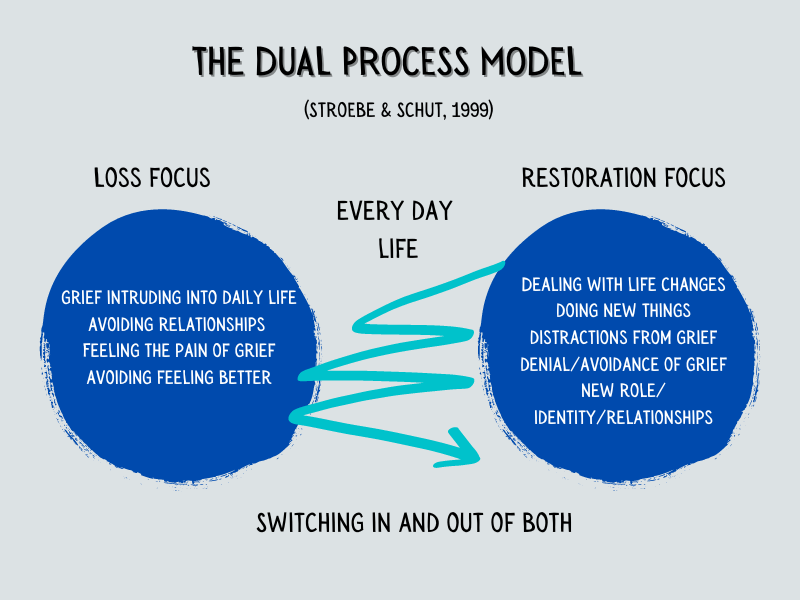

Learning to move forward with loss is an disorientating experience. Not only because you have to be OK with not being OK, and navigate the world with a broken heart on your sleeve. Also there’s no map, instructions, guidance, or linear journey plan to tell you how to do it. At times this uncertainty is brutally confusing. According to my Cruse councillor I’m experiencing the dual process of grief. Diagrams and theories aren’t everyone’s ideal remedy, but I always like it when someone shows me the scientific evidence for a theory I’ve already experienced.

This model defines two states of stress in bereavement - a loss-orientation and a restoration-orientation. Both of these emotional and practical zones require the ability to cope, and so there’s a third space which looks like a zig-zag between them in this image. In child bereavement they call it “puddle jumping” because children naturally protect themselves from the uncomfortable emotions in either puddle. For adults it’s more confusing, because life is more complex and our bodies resist the natural need to protect ourselves. This is when the bereaved need to take a break from coping, fly a kite, splash in puddles, or dance in the rain.

The middle zone makes me think of how jet pilots need to learn to adapt to extreme acceleration. A rapid rate of change in velocity means fighter pilots risk becoming disorientated, they loose consciousness during G-force manoeuvres. It must be a nauseating, high adrenaline experience. I’m Maverick and I’ve lost my wingman. My manoeuvres through grief are completely made up, I’ve no idea what I’m doing. Like Top Gun, I’m driven by my values, and my need for speed. Where others see rules, I look for the gap. But any strength can become a weakness.

Loss stressors come from focusing on the person who’s gone - it’s the familiar part of grief, from processing the loss and remembering the relationship with the person who’s died. For me, these pressure points are all in the past. I need and want to remember them, and it’s horribly uncomfortable to stay in what was. Photos of everyday life with Mark, recordings of his voice, videos of the way he moved are all triggers which often I’m unable to cope with. I yearn for his presence in a room, imagine what he would say, and I feel how much he would love this moment. Like Maverick in the film Top Gun, I regularly plead for guidance and advice from my dead wingman, “Talk to me Goose.”

Restoration-oriented stress happens while making changes to adapt to the loss. Like changing roles and finding new ways to do things. Doing the things Mark used to do is less painful now (I put up some coat hooks the other day). This task-based state is often comforting to me, I like staying here, but it doesn’t help me to process my emotions. I also often feel lonely and isolated in this zone. It’s an otherwise “normal” world where I am alone and feel easily forgotten. Adaptive, practical steps feel like progress yet leave a perilous contrail in their path. Moving forwards is bewildering some days, small changes can seem insurmountable. On other days I get huge surges of energy from completing a mountain of objectively defined tasks. Then I’m disgusted with myself for planning any glorious thing without him, wanting only for him to feel the satisfaction of our success.

My Maverick

There’s an emotional rebound from rebuilding everyday life after loss. It’s the more complex part of grief for me, because it’s harder to predict, and it undermines the joy or pride I might feel when people say, “You’re doing so well”. Like Viper says in the film after an unforgiving aerial training exercise, “There are no points for second place.” I don’t want to be doing well, because I don’t want to be on this training programme.

Even on the days when I can imagine a different life, believe in my ambition to be OK, plan big things for the future, or simply feel normal, my heart and body are always in the pilot seat. My pace and progress is twisted by G-forces beyond my control. I’m oscillated by air traffic out of my control. Just as the commanding officer said to Top Gun, “Your ego’s writing checks your body can't cash." Only by continuing to pay close attention to my dynamic state, adjusting my expectations, and learning to adapt can I begin to trust myself in these G-force moments. I want to feel the unfettered, freedom of soaring joy again, and yet I have to accept that it may never be mine. Never is a very, very long time to cope with anything. To last the duration I’m going to have to find ways to gain any control of the joystick and learn to fly both at super slow and ultra fast velocities.

I might not like it - moving forwards will make me feel angry, sad, disgusted, and lonely. If healthy grieving is a dynamic process between respecting loss and rebuilding life, then my capacity to cope is going to be increased by addressing these feelings, in any way I can. It might require confronting the loss, and then avoiding it. Being practical and level-headed one minute, while raging at my invisible aggressor the next. Crying into my coffee, while simmering with rage. From the outside I might seem chaotic or unpredictable. I don’t know; I’m on the inside, in the cockpit, close to lunacy. From where I’m sat there’s no wrong way to do this, I can only go wildly with intuition.

uffff. thank you for sharing this Rachel. I had to read this one in two parts again, as it was a lot to take in, and feels incredibly important. I didn't know Mark had dreams of being a helicopter pilot... so after you built those beautiful and fitting aviation metaphors, the last image was a sucker punch. Goose smiling back at me... The jumping puddles figuration feels very apt: neither 'puddle' is comfortable and the moment mid-air between them is disorientating. I love you very much.